Marginalized communities are most affected by the consequences of the climate crisis – in cities both in the Global North and the Global South. While the state often neglects them, community organizations have started to address these issues. In Sunset Park, New York, the neighborhood organization UPROSE is mapping the effects of climate change in the area, educates community members about possible risks and proposes alternative plans for urban development.

Sunset Park is a neighbourhood in Southwest Brooklyn. It borders the Bay Ridge channel, a body of water along which stretches an industrial area with a shipping terminal and several warehouses. The neighbourhood lends its name to a park in an otherwise densely urbanized district offering views of downtown Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the wider bay area. The history of Sunset Park has been shaped by the arrival and presence of immigrant communities, particularly from Latin America, which are still growing today.

Along a side street of one of Sunset Park’s main thoroughfares lies an unassuming building. The upper floor of this building is home to the United Puerto Rican Organization of Sunset Park - Bay Ridge (UPROSE). Founded in 1966 during the civil rights movement, “UPROSE was formed by local people in this community, which was basically working class Puerto Ricans”, Esmeralda Simmons, a board member, recounts. It was a time when Puerto Ricans wanted more of a say in decisions affecting local communities, in particular concerning housing, transportation, development, and youth.

David Williams directs the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Climate Justice Programme in New York.

Fighting Gentrification

In the 1970s and 80s, the close proximity to Manhattan was one of the reasons why Sunset Park became the subject of numerous gentrification efforts vehemently resisted by local communities. Industry City, a waterfront redevelopment project in Sunset Park caused significant increases in rents and living costs in the area. However, a rezoning application to further expand Industry City was withdrawn after significant resistance from local communities and lawmakers.

In spite of some successes at blunting the impacts of redevelopment, Brian Gonzalez, a local teacher and activist at UPROSE, explains “it’s become so much more expensive to live in Sunset Park in recent years”, and that demographic shifts have been occurring. Close community engagement has therefore been the key principle of UPROSE’s approach: “Who are you going to trust the most? You’re going to trust your neighbours”, says Gonzalez. Regular community engagement meetings are held to understand and relate concerns of the community to city officials.

In recent years, those concerns have been increasingly related to climate change, particularly heat stress in summer, and flooding all year round. The impacts of these extreme weather events have been felt most intensely in those areas in the community that are marginalized in terms of wealth, income, as well as access to transport, education, or emergency services. As a response, UPROSE began conducting community education programs combined with block-to-block organizing, mapping exercises, as well as offering guidance on emergency responses.

Concerns of the Youth

It was also the guidance of young people who influenced the shift in focus of UPROSE toward environmental and climate justice. “Young people were concerned about open space, they were concerned about a planned power plant the size of three football fields, they were concerned about the fact that the community was in a lead belt”, explains Elizabeth Yeampierre, executive director at UPROSE. Combined with the economic disinvestment that was happening not only in Sunset Park but in various communities of color throughout New York City, this required the broad scope of UPROSE’s work around the intersection of social, racial, economic, environmental, and climate justice.

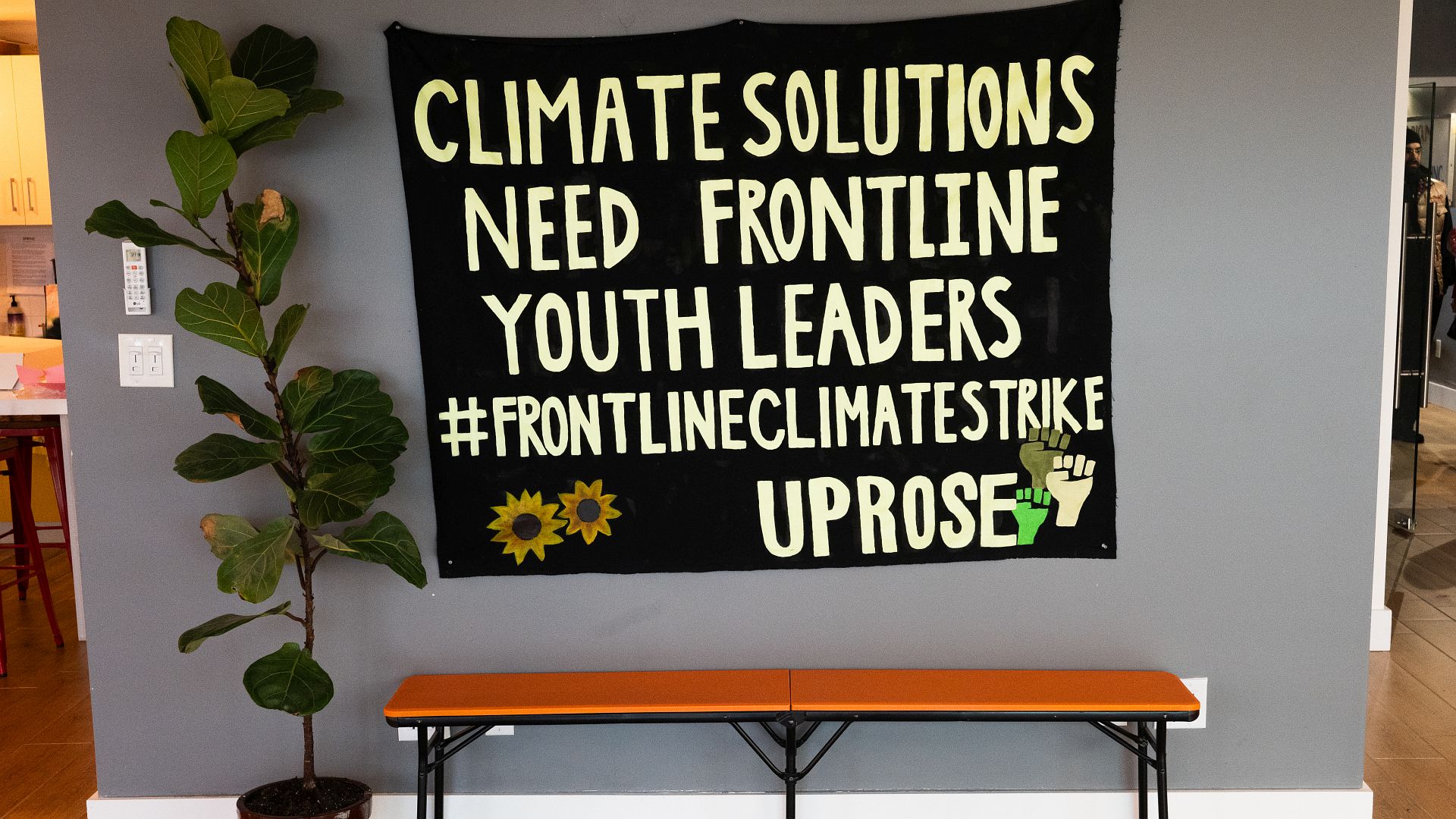

Creating engagement opportunities for youth and securing a seat at the table is critical, emphasizes Allahji Barry, a youth activist at UPROSE. According to Barry, past accomplishments have generated the perception that UPROSE truly represents community interests. This has also helped in establishing an inter-generational team, whereby the broad age spectrum of Sunset Park is represented within the organization. In addition to a focus on social media as a tool for communication and outreach, youth initiatives have ranged from native plant workshops to block parties and art builds. “Art is central to us. Art is how we build community”, explains Yeampierre.

An Alternative Vision for the Area

Sunset Park is a neighbourhood dominated by manufacturing and industrial activities, employing many of its local residents. “How can the industrial sector start serving our needs instead of killing us?” was a key question that UPROSE grappled with from the very beginning, according to Yeampierre.

UPROSE found its answer in advocating for green manufacturing, building for climate change mitigation. A key component of this is GRID 2.0, a planning alternative for decarbonizing the local economy by strengthening green economy actors and increasing protection from extreme weather events. The plan is a multi-stage community-driven alternative vision of how to implement the first foundational phase of a just transition. The timeframe for implementation extends to 2035, and the plan can also be adapted and replicated for other neighbourhoods and cities.

As the plan explains, the initiative illustrates the broad scope of community engagement towards devising viable alternatives to existing city planning in the reimagining of space in a densely urban community. Whether stakeholders choose to implement its recommendations remains to be seen.

New Challenges

UPROSE has faced challenges over the years. Adding to tense urban relationships stemming from a history of racism and white supremacy, the willingness of administrations to work with community organizations has varied significantly, and many of those in positions of influence seem to have failed in fully grasping the extent and urgency of intersecting pressures faced by communities across New York City.

Government officials were prone to “using conventional methods for an unconventional problem”, as Yeampierre says, not recognizing the deep structural changes necessary. Neither was intersectionality of the crisis acknowledged, criticizes UPROSE, in particular patriarchal systems of institutional decision-making preventing equitable progress, nor the need to hold those to account who were driving and profiting from climate change. An additional source of tension have been “big green organizations with heavy footing, helicoptering into our community and supplanting local leadership”, adds Elizabeth.

Cities across the world are on the front lines of the climate crisis. Dense cities are the places where most people live, and where climate change impacts create the most harm, particularly in marginalized communities. At the same time, cities are also the sites where mass consumption and emissions are concentrated. Community engagement is critical to reduce risk and implement a just transition.

While each neighbourhood and the challenges they face are unique, there are key principles upon which community engagement depends, and which apply to various contexts and stand the test of time. In one of UPROSE’s meeting rooms, the Jemez Principles for Democratic Organizing are pinned to the wall. Developed by Environmental Justice groups in the 1990s and decided upon at a meeting in Jemez, New Mexico, in 1996, they serve as one such guide for learning, collaboration, and building global solidarity both within and between cities. Principles such as these will be crucial in a future where emissions continue to rise, and the effects of climate change will become more and more devastating.