On 14 June 2023, the fishing boat Adriana sank in the Mediterranean Sea off the Greek coastal town of Pylos on its way from Libya. It is estimated that over 600 refugees, mostly from Pakistan, drowned. Survivors and human rights activists blame the Hellenic Coast Guard (HCG) and the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, Frontex, for the deaths.

Dimitra Andritsou works as a Senior Researcher at Forensis Research Group.

Yet one year on, no one has been held accountable for the drownings, and little has changed in the European border regime. Will justice ever be within reach? To mark the anniversary, the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Boris Kanzleiter spoke with Dimitra Andritsou of the Forensis Research Group, which, together with the independent Greek research portal Solomon, German public broadcaster ARD, and the Guardian conducted an extensive investigation into the case that won the European Parliament’s Daphne Caruana Galizia Prize.

The Hellenic Coast Guard (HCG) claims the Adriana capsized because of “commotion” on the vessel. Your research proves the HCG’s responsibility. What really happened on 13 and 14 June 2023 in the Ionian Sea off the coast of Pylos?

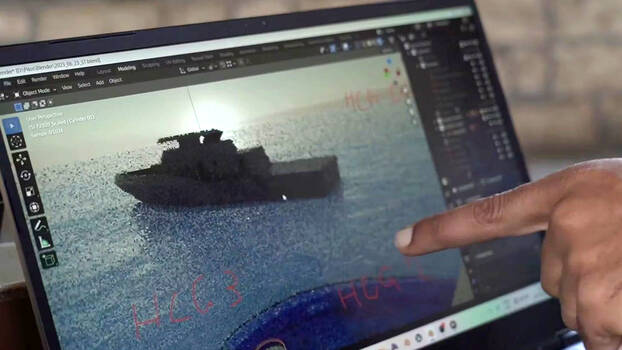

On 14 June 2023, the fishing boat Adriana, having left Libya for Italy with hundreds of migrants on board, sank inside the Greek Search and Rescue (SAR) zone in the Mediterranean Sea — what would become the deadliest migrant shipwreck in recent history. Contrary to official accounts of the Hellenic Coast Guard, our digital reconstruction of the incident indicates that over 600 people drowned as a result of actions taken by the HCG.

More specifically, on 13 June, and while the boat was on its fifth day of travel, it transmitted several distress signals to activist and monitoring groups, such as Alarm Phone, suggesting that they were in urgent need of help. All relevant authorities, including the Hellenic Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (JRCC), HCG, and Frontex, were aware of the state of the boat from early on that day, having captured it through different aerial surveillance assets.

In the night, and after several hours of drifting, the HCG patrol vessel ΠΠΛΣ 920 arrived at the location of the boat, at which point they discharged all commercial vessels earlier deployed in the boat’s vicinity for assistance — rendering the HCG crew and the people on board of the fishing vessel the sole witnesses to what was about to ensue. According to survivors, and consistent with our mapping analysis, upon arrival the HCG instructed the boat to follow them westward towards Italian SAR waters, where they would be handed over to the Italian Coast Guard, until the engine of the fishing boat stopped working.

Survivors then report that when their boat’s engine stopped, the HCG vessel approached them, a masked man tied a rope to their railing, and they attempted to tow the migrant boat twice. The first time, the rope snapped. The second time, the HCG pulled even faster, causing the migrant boat to capsize. Making matters worse, the HCG retreated from the scene in such a way that created waves, which in turn made survival in the open sea more difficult, leaving survivors to fend themselves for a period of 20–30 minutes. Out of the approximately 750 people on board of Adriana, only 104 survived and 82 bodies were recovered, with the remaining people are missing to this day.

Our analysis also suggests that, after the tragedy, the HCG attempted to distort the narrative around the event by providing inaccurate and conflicting information regarding the migrant vessel’s location and speed, failing to record the operation even though they had been specifically instructed by Frontex to do so for all operations two years earlier, and confiscating the survivors’ mobile phones — which were protected in waterproof cases, and contained visual documentation of the incident. This clearly illustrate the HCG’s responsibility for the shipwreck, as well as coordinated attempts at a cover-up.

What role and responsibility do you see for Frontex in this disaster?

Over the last two decades, numerous reports from international human rights organizations and investigative journalists have documented the complicity of Frontex in systematic human rights abuses, violations, and cover-ups along the EU’s external and internal borders. As regards the proliferation of such violations in Greece and the role of Frontex, despite purported statements of “establishing an action plan to right the wrongs of the past and present”, the EU border agency’s shortcomings in doing so are evident in the case of the Pylos shipwreck.

This type of criminalization of migrants has been a common tactic of the Greek authorities for years.

In early 2024, the European Ombudsman, Emily O’Reilly, released a report examining the role and responsibilities of Frontex in the deadly shipwreck, highlighting “obvious tensions” between Frontex’s fundamental rights obligations and its support to member states in border control — in this case, Greece. While the unseaworthiness of the boat and the clear level of distress of its passengers was known to Frontex from early on, and despite the fact that Frontex was fully aware of the longstanding troubling history of Greek authorities’ non-compliance with fundamental rights obligations, they failed to highlight and uphold the urgency of the situation and intervene in a timely manner in order to assist the people in distress. The fact that Frontex offered to assist the Greek authorities by sending aerial assets to the scene three times and received no response, should, in fact, have been a decisive factor to engage in further actions to prevent what would become one of the most devastating shipwrecks in the region’s recent history.

That also brings us to another crucial element in relation to Frontex’s aerial surveillance as a tactical operation. As documented by Border Forensics and Human Rights Watch, the very use of aerial surveillance for documenting migrant boats in the Mediterranean Sea, contrary to Frontex’s claims of “saving lives”, is often documented for doing the exact opposite: as an example, by facilitating the interception of hundreds of people by the Libyan Coast Guard who are then returned to Libya — another border guard agency tasked with “controlling irregular migration” on behalf of the EU while engaging in systematic and widespread human rights violations and abuses.

Back in 2021, Amnesty International published a report stating that pushbacks are part of Greece’s “de facto” border policy. Can you explain what pushbacks are and how they are used by the Greek authorities today?

At Forensic Architecture and Forensis, we have been investigating the systematic and widespread nature of pushbacks at the Greek-Turkish borders — more specifically, across the Evros/Meriç river and in the Aegean Sea — for more than five years. Migrants and refugees making the crossing either at sea or through the river are intercepted in Greek territorial waters, or arrested after they arrive on Greek territory, beaten, stripped of their possessions, and then forcefully loaded onto rubber boats and returned to Turkey — without the chance to apply for international protection, contrary to the 1951 Geneva Convention and other regulations of international law.

At the Evros/Meriç river, this is a very systematic, and to a certain extent, organized practice that involves a hostile infrastructural nexus of police stations, border guard stations, and detention centres, but also a diverse network of actors, including police and military officers, and sometimes civilians and foreign personnel. In the course of that practice, migrants suffer egregious and well-documented violence, including beatings, sometimes amounting to torture — while a second layer of violence also emerges which is inflicted through the natural elements and the geography of the river.

Similarly at sea, and in particular since March 2020, a new method of violent and illegal deterrence has been practiced: people are loaded onto life rafts with no engine and left to drift back to the Turkish coast. “Drift-backs”, as the practice has come to be called, have become routine occurrences throughout the Aegean Sea, often resulting in injuries and drownings. Today, the scale and severity of the practice continues to increase, reported from the coast of the Greek mainland and as far south as Crete. We documented over 2,000 separate cases of such “drift-backs” spanning a period of three years between 2020–2023.

The Pylos shipwreck is a direct result of this violent and illegal practice becoming a “de facto” border policy of Greece as well as other EU and non-EU states. Alongside the fact that the HCG’s towing of the boat towards the Italian SAR in an attempt to deter it from landing on Greek territory led to more than 600 precious lives lost, another crucial dimension of the inhumane and lethal nature of the European border regime emerges: the fact that the systematic and widespread practice of pushbacks has led to people opting for deadlier routes — such as the Calabria sea route — in an attempt to bypass Greece, knowing that there they would be subjected to atrocious harm and violence and likely pushed back to unsafe third countries.

How is the crime being dealt with legally? What investigations has the public prosecutor's office initiated? What charges have been filed?

In a typical sequence of events, one of the first legal actions undertaken by the Greek authorities was scapegoating and criminalizing survivors: only a few days after the shipwreck, nine Egyptian survivors — the Pylos 9, as they came to be called — were arrested, placed in pre-trial detention, and charged with membership of a criminal organization, smuggling aggravated by human deaths, intentionally causing a shipwreck with fatal result, and unauthorized entry into Greek territory. Instead of receiving support and care for the harm the Hellenic Coast Guard subjected them to, they suffered more harm.

This type of criminalization of migrants has been a common tactic of the Greek authorities for years — deployed so extensively that it now constitutes what Legal Centre Lesvos has called an “industry of criminalization” — in an attempt to absolve themselves of responsibility and distort the narrative around their own systematic human rights abuses.

This quest for justice is not restricted to a narrow, legal term, but grows out of an understanding that systemic injustices require systemic redress and change.

Only a few weeks ago, in a court hearing held in Kalamata on 21 May 2024, the court acquitted the nine defendants on the charges of smuggling and illegal entry, while also accepting an objection by the defence lawyers that it lacked the jurisdiction to judge the charges of causing a shipwreck and membership of a criminal organization, as the incident took place in international waters. However, in what seemed like a vindictive attempt to prolong their suffering, the Pylos 9 were placed in administrative detention — it was only after repeated objections by their legal representatives that four of them were released, while the remaining five remain detained.

On the part of the civil society, a number of independent organizations, as well as political and administrative institutions such as the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, the LIBE Committee of the European Parliament, and the Greek and the European Ombudsman have asked for a transparent and thorough investigation into the shipwreck. Importantly, in September 2023, 53 survivors filed a criminal complaint against the responsible officials of the Greek authorities before the Naval Court of Piraeus, demanding an effective investigation into the circumstances of the shipwreck.

The Naval Court, which has jurisdiction over the HCG, opened a preliminary investigation almost immediately after the shipwreck, in June 2023. However, that investigation remains at preliminary stages, while a request by the court prosecutor for forensic analysis of the HCG’s officers’ phones — only seized several months after the tragic incident — is still pending.

More than 600 bodies lie on the bottom of the Mediterranean. What demands do the victims’ relatives and human rights organizations have?

The friends and loved ones of the victims, the survivors, and their supporters, continue to fight for complete clarification of the circumstances of the shipwreck, for justice, and for political consequences and accountability. As one of the survivors we interviewed said, “I lost my friends, my cousins, my brother-in-law. I need to find them some justice.”

This quest for justice is not restricted to a narrow, legal term — seeking singular criminal responsibility for a singular incident — but grows out of an understanding that systemic injustices require systemic redress and change. The devastating shipwreck of Pylos is not an isolated incident — it is the result of years of lethal and inhumane “border management” and border-making enforced and sanctioned by Greek and EU authorities and sustained through different manifestations of border violence and a systemic culture of impunity.

An expanded notion of justice means doing everything in our power to prevent such a tragedy from happening again — in Greece or elsewhere — by bringing an immediate end to the vicious border regime and its enablers that continues to inflict perpetual pain, suffering, and harm on racialized people and communities.